In the next few pieces, I will aid you in learning the arcane arts of building up a hex map, using my previous article’s BLEAKWOOD to do so…

Together, we will go from the cantrip level of “some places and a couple factions,” to the towering eldritch accomplishment of being able to effortlessly run adventure after adventure in an area you and players will become intimately familiar with and connected to.

(There might be an article or two between entries in this series)

Before we dig into how I use my hex powers of necromancy to put the “flesh” on a “skeleton” hexcrawl, I wanted to discuss the burning, super-important question of “why use a hex map? Why not just scribble up a map on plain ol’ blank paper?”

Well - for one…

I love hex maps.

Just putting that out there at the beginning.

To me, they scream “old school,” and there’s just something about those perfectly fit together little shapes - whether you’re a flat-top or a sharp-top person. I give my allegiance to flat-top hexes, but have occasionally turned traitor and used them in their sharp-top position.

But it isn’t *just* an aesthetic choice for me - it’s about how useful they are from the minute I start worldbuilding all the way through running the map at my table.

A stark, milk-chalk white piece of paper is intimidating to me.

Where do I begin?

What do I put where?

What is the scale?

Is someone on Reddit going to make fun of the fact that my rivers aren’t geologically correct and that I’ve created a water table that somehow defies the laws of map-making???!!!#@@!!

Hex maps allow me to, as the bumper sticker says, “think globally. Shop locally,” as it were, by selecting smaller areas, and “going deep” in order to provide a more meaningful connection to my game world both for myself and the players at my table.

For me, success at running a game means more than just entertainment, although that’s obviously the number one - that folks have a good time.

But more than that - I believe we want them to feel *connected* to the world, familiar with it. There’s few better feelings than when your players have an “aha” moment, drawing mental lines between places, events, and people in your world because they *know it.*

And, more than that - we want them to feel invested in the world, and in the game. To create that, I have to make it memorable, and in my opinion, the best way to achieve this is to make it feel, if not “real,” at least “moving.”

To create regions and places that have shared history, NPCs that are products of their environment and so on, allowing for players to truly engage with the texture of my game and game world.

Also, we have to do this without spending all our time prepping. Although I do love worldbuilding and prepping, the ravages of family and career have polymorphed me into a GM who relies heavily on faster, less often prep sessions in order to spend more time playing than scribbling.

This is where the hex map comes in.

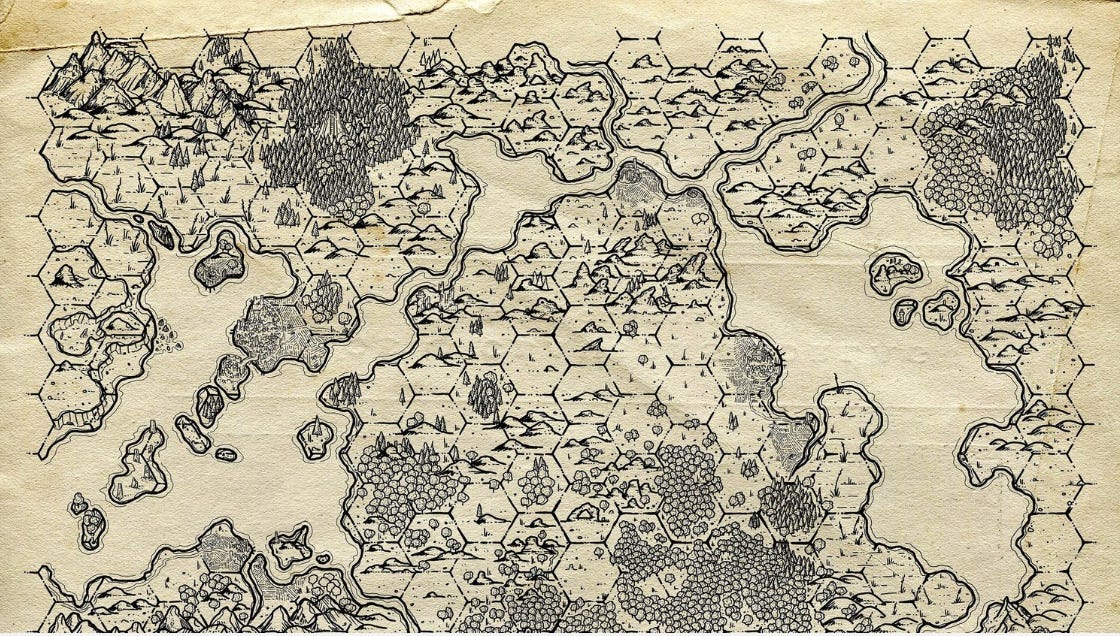

(Above is a beautiful example of a hex map from the inimitable Dyson Logos)

I can do short burst prep sessions that allow me to sketch in concepts, run games, and deepen things as I go, creating new reasons in-game to keep the players *wanting* to stay, to delve deeper as it were, into the region or area.

The longer we can squeeze GOOD sessions out of a hex area, the more successful we were in its creation.

Not only this, the hexes themselves act as guidelines for me to place things. Instead of going “wherever” on a blank page, I can use each hex as its own mini area to fill in and enrich. It acts as a divider between “interesting things,” and I generally put *something* in each hex - eventually.

This means four things:

Layered hexes

Rumors

Interconnected and active NPCs and Factions

TABLES!!!

First - the layered hex.

Many hex map magi are probably familiar with the concept of layering a hex. For the uninitiated, this essentially means breaking each hex into (at least) three “layers.”

The first layer is what is most obvious, or striking - what the characters are the least likely to miss if they are simply “passing through.” This means obvious landmarks or highly visible points of interest (POI). Things like forts on the road, giant trees, rock formations, or a GODDAMN FLOATING ISLAND or whatever.

Stuff they’re just…gonna see.

The second layer is going to be stuff that’s not readily apparent, or that will require time spent exploring that single hex for a while. Poking around, walking through the woods, climbing that rock formation to see what’s on top. Basically, this is the INTERACTION layer - it requires agency and action on the players end to discover, but it isn’t hidden from them. They just have to look around a while.

The third layer is hidden from them. This is the secret layer, and it is where you will often create some true magic. Secrets won’t always be discovered on the first, second or even third pass through a hex. Often they require specific knowledge on the players/characters part in order to find them.

Perhaps in that hex with the rock formation (L1), they climbed up to the top of it and found, on “layer 2” (L2), a standing stone at its top, covered with strange runic letters - they can’t read them and have no idea what’s being said.

In another hex, the explore a dungeon or ruin, and find some piece of treasure (a book, scroll, whatever) that has a key to decipher “the strange runes from the standing stone.” They return to the standing stone with their new info, and see that the stone is actually a doorway of some kind - their translation also leaves them with another puzzle to actually get it open, the answer of which lies on “level three” of another hex.

This kind of interconnectivity between hexes will allow you to surprise your players with the level of discovery they can make, and it encourages them to explore the heck out of your region. Every landmark they see becomes something they want to explore, and they begin to think in terms of “what is described to me isn’t just window dressing. Each thing I hear about has the potential for adventure, treasure, advancement, entertainment, etc.”

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t lead with your best foot forward - I *want* the players to discover the little hidden things in my world. It doesn’t do me much good to have it and never get to show it.

I utilize little clues about things.

Perhaps the standing stone on the rock formation is referenced by the mad hermit in hex 27, or what have you. This is another key to region design that most are familiar with - the rumor.

NPCs are quest givers not simply by “the wizard hires you to explore the abandoned tower” sort of thing, but simply by mentioning things in passing:

“My father always said there was a strange stone up there on Eagle’s Roost - he and the young men from the village used to climb it to impress their sweethearts. Until one day - they said the stone…opened!”

Things like this also make your area feel alive, like the people actually live there.

Try to connect at least one or two rumors to your secret layers.

This all sounds like a ton of prep, I know, but it doesn’t need to happen all at once. You get a basic region sketched in, and have a few rumors about this area or that one, and its off to the races, allowing you to throw more ideas into your hexes as you go, or when a good idea pops in your head in the shower.

Your factions are important, as well.

This is another thing that you can add to - often PCs are unaware of factions until they reveal themselves through gameplay and occurrences that may even be triggered by the PCs themselves.

At the start, I shoot for three, because this allows me to create factions that are connected, possibly at odds, or tangled in some kind of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” bit.

These factions should, at the least, have a fast couple of notes:

What do they want?

What resources are available to them?

What are their plans to get it?

These plans can get layered and complex, but ultimately act as a simple way for you to keep track of what your factions are doing during and between gaming sessions.

I use basic dice rolls to see “who’s winning,” and often this will color the next game as factions wax and wane. All these little “subsystems” in my game aren’t distractions from the game - they are the game.

Other adventuring parties who are racing against the PCs to complete a job. Ruthless nobles who want to hire the PCs to re-establish order in the village. Necromancer kings in twilit realms under the earth…whoever they are, they want something.

Finally (although, not really, because this will be an ongoing series), the trusty and beloved random table will save your backside time and again during a sessions where things go stale or off-course.

If you take a ganders at the initial encounter table in BLEAKWOOD called Road Hazard, your mind immediately begins to extrapolate some sort of plot from it.

I personally don’t know what that plot will be - it depends on the order in which PCs encounter these things, what they do about it, and what pops in my head as an outcome.

Who is the hanged man with a map stuffed in his mouth?

It can be presumed that the wagon with cartographer’s equipment is connected to him in some way, perhaps?

Who is the Piper, and what the hell are these giant wicker men that are popping up all over the place?

I try to make encounters interesting, and I always roll reactions - things I might have thought would be allies or potential friends become threats instead. The game moves where it will.

I recommend borrowing, stealing, mashing up and hacking several encounter tables together or make your own - you can utilize my method for making good tables HERE.

In the next article on this topic, we will take a look at some of these concepts in action, using BLEAKWOOD as our base, and expanding on it.

I hope you found something useful here!

Keep your blades sharp,

- Castle Grief

Again, lovely article. I love the quality of the content of your pieces! Thanks for sharing.