This week, I got a comment that read:

“I would love an article about your work flow.

How you spend your time when you set aside time for RPGs and how you manage your own creative output. I’m ADHD and a forever DM.

I find I end up putting so much effort on my improv skills because I don’t have a map of how to properly plan out the execution of all that goes into setting up a game.

I love the Dungeon23 movement because it breaks down mega dungeons into bite sized chunks I can understand.

I’d love to know how you went about creating the west marches setting, the Mork Borg module and your weekly games.”

Andrew, I’m going to do my best to answer your question, here, breaking it down into a few sections:

I: How to create a setting the easy way

II: How to create a modules/adventures

III: How to run a weekly game

Each one of these is a weighty enough topic to warrant its own article, so I’ll do just that.

Ok, so -

Creating a setting can be one of two things: a fun and exploratory creative endeavor that is enriching for you, fun for your players, and a great outlet for the times you’re not playing but want to work on something game related…

OR

A massive time sink that you don’t even wind up using the way you thought you would, leaving you overwhelmed, frustrated, and burned out.

Nobody wants that, so…

The first question to ask yourself is “why?” By this I mean - whether or not you need to create a setting in the first place.

In much the same way as creating a ruleset isn’t necessary when there are so many great ones to choose from, you might be better served simply using a setting, or pieces of one, that is already published.

This last is an important note: you don’t have to use the entire setting, or learn every nook and cranny. Just enough to run your next game - if you have to improvise something, who cares? Now that’s canon for *your* version of the setting.

This is the same as using a ruleset that exists and then house ruling it - eventually, it becomes *your* ruleset, just as settings you start out using get changed and become your own weird and wonderful Frankenstein’s monster of all the best stuff you like that you’ve ever seen anywhere and cobbled together.

This is half the fun.

For some, however, running an existing setting can either be too much or not enough.

Too much existing material to concern oneself with, or not fulfilling enough to their need to create something that is really “theirs.”

So, if you do feel the burning need to make your own setting, here’s a couple things to keep in mind.

1) Resist the urge to go full Tolkien. You don’t need to know what language the indigenous people of your far southeast archipelago culture speaks if your players are unlikely to encounter that culture for a while.

Worry about their immediate surroundings, and the things they’ll *need* to know for class information and gameplay, and the things they’ll *want* to know to immerse themselves. You, like every DM before you, will possibly be surprised to learn your players don’t care as much about your setting’s details and lore as you and just want to have fun. This doesn’t mean creating a believable and engaging world isn’t part of that, just that they will forgive you if you have to make some things up on the fly when they ask a question you weren’t expecting.

There’s a million good articles out there on making a fantasy sandbox, or building a hexcrawl and so on, and most of them agree: start small. Like, really small. I always see people in various subreddits working on their starting map for their players and it’s like 50 dungeons and adventure sites, multiple towns, 100 square mile area keyed in and so on, and I think…

Holy shit, that’s a lot of unnecessary work!

If they enjoy it, more power to them, because it can be a ton of fun, but for those with tight schedules and a finite amount of time to put into this, efficiency is the name of the game.

In the Kragov region of my own ongoing campaign setting, which by now spans several different countries and cultures, the beginning campaign was played for many sessions on the same sheet of hex paper, and the characters visited very few sites off the beaten path.

We had a wonderful time playing there, and I was able to spend my time mostly on the places they spent their time, deepening the feel and texture of the parts of my setting they were actually invested in and engaging with.

The prep is to create some area and options for your players, in a good old school game, not a railroad - the games are to give you data on what the players are enjoying most, and allow you to use that data to develop things in a good direction for them.

Don’t “break the bank” of your creativity and mental energy by doing so much worldbuilding that when it comes time to play you have a 500 year timeline of the obscure religions but no *good adventuring options.*

Remember, adventures - that is, challenges, conflicts, and problems for your players to solve - are the heart of the game. The world it happens in is important, too, but a good story trumps knowing how to pronounce words in Elvish.

2) What sort of game are you trying to run, anyway?

This is another worthwhile question to ask *before* you sit down to hammer out your setting meisterwork…often, we have an idea for a world and all this complicated stuff, when the simplest opening information is actually:

What are we going to be using this for?

What I mean is, it doesn’t make sense to work on establishing all the court intrigue and drama for your big city if you and your players mostly plan to run a megadungeon.

Likewise, if you had a city campaign in mind, with lots of mystery and politics and power-struggles, then it’s a lot less important to know what’s going on in that old ruined dwarf city over there on your map.

You might never wind up out of the city, so the only details you need to know are cursory things that explain the stuff the players will actually need to know.

There’s also the chance that *gasp* you’ll run a few games in this setting and either the campaign will stall or you may move on from the play style or what have you, making all these hours, not a waste, but something you might not get to use as much as you imagined.

In these potential cases, it’s much better to have invested the time in a convincing sketch than a full-on photorealistic painting, as it were.

In my own world (IT DOESN’T EVEN HAVE A NAME, AND NONE OF THE PLAYERS HAVE EVER ASKED!!!), I began by sketching out the main area play would happen in, the two main realms that would be talked about/most of the regions people come from, a basic idea of why they didn’t like each other, a few lists of names, and then focused all my attention on the local area and fun adventure seeds for a sandbox.

You can see the hexmap of the original area HERE.

I short-cut a lot by basing this entire region on medieval Wallachia/the Carpathians, and took tons of inspiration from my and my players favorite black metal albums.

The main country is even called…Walakia. This way I can just look up words, towns, names, etc from the time and region and change them a tiny bit and they have a convincing feeling. It also saves me an immense amount of time and brain power to do other stuff that matters more.

As our campaign went on, and characters were introduced from further lands, I would provide them the absolute basic information on where they were from:

“Your homeland is a massive steppe far to the south, and across a sea from the southern coast of Walakia, called The Kyrg. Your clan were mostly horse-traders, raiders and warlords, and despise farmers as a general rule. Here’s a list of names to give you a feel for what you might choose.”

In this way, I not only expanded my world, which now includes many different countries and themed places, but also opened it up to play many, many different types of games. This way I never have to stop using the same campaign world, I can simply develop a new area and play there, and players are always excited when they hear a reference to somewhere they recognize and realize we are playing in the same world.

I’ve done this through several different rulesets we’ve experimented with and a variety of play styles from dungeon crawling to domain-level play.

3) What do you want your world to feel like?

I referenced this above - this is a trick question because in my opinion it is much too big to answer, or need to be answered. A better question is: what do you want your opening play area to feel like, and is there another place nearby enough that its people will be interacted with to need to have a cultural/vibe contrast?

My new game, Kal-Arath, takes place in the same *world* I’ve mentioned. It is a different *culture* within that world, and because it is so isolated from the rest of the world, it is ok for it to feel *extremely* different.

A massive grassland complete with dinosaurs, forbidden monasteries, blood-drunk monks, demon lords, massive wooden siege engines sailing across the plain - I wanted it to *feel* very specific, and evoke a feeling of sword and sorcery more than the darker fantasy medieval grit of much of my world.

To evoke this, I began to look at pictures of places, people, animals, and so on. I started to look at languages that already existed and mix them up with other ones.

These “existing” cultural mash-ups provided me with a culture that felt like throwing Rohan/Anglo Saxon horse culture into a blender with the Mongolian steppes if they were built around a religion that took the recognizable elements of Buddhism and made it demon-worship.

Pretty weird mix, but it allowed me to short-cut a TON of work, by being able to explain to players that a monastery looks like “equal parts mead hall, stave church and Buddhist temple.” Their imagination can do the rest, and I’m able to do the same with how the people dress, lists of names, cool titles for spells, and all the rest.

In other words - pick stuff you know and like from movies, magazines, artwork, and throw it in a blender. There’s nothing new under the sun, and the best artists and creators are those who steal and take inspiration from *everyone.* Don’t be afraid to shake things up and make something really weird, as long as it’s not boring, and your players are excited to explore it.

As always, the real question is: does this sound fun? Does it make me and my players go “oh, hell yeah, that’s cool!” Does it make for fun around the table (or digital table?) And, for you, the GM and worldbuilder - did you have fun making it?

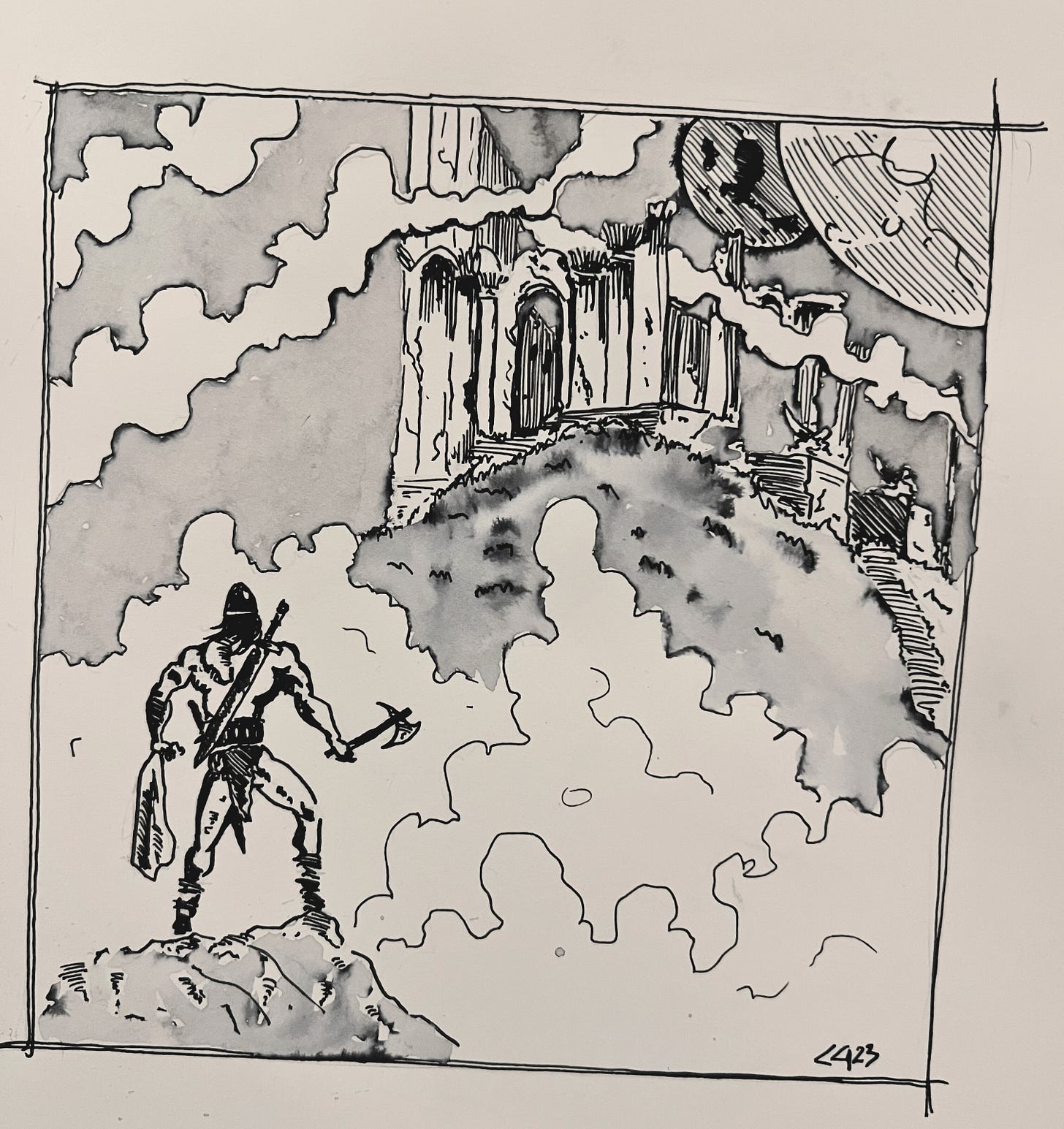

If it can check those boxes, you’re doing great. Keep at it, and keep your (creative) blades sharp!

- Castle Grief